NEW PRIVATE PAIR RELEASED AT USPTO: The good folks at Rethink(IP) (Stephen Nipper and Matt Buchanan) provide a rundown on the USPTO's latest release on the Patent Application Information Retrieval (PAIR) system. Four highlights were identified on the new system:

NEW PRIVATE PAIR RELEASED AT USPTO: The good folks at Rethink(IP) (Stephen Nipper and Matt Buchanan) provide a rundown on the USPTO's latest release on the Patent Application Information Retrieval (PAIR) system. Four highlights were identified on the new system:

1. Web-Based Digital Certificate Security- requestors no longer have to download USPTO Direct software. Log-in can be done through any browser (FireFox hasn't been completely vetted yet) by using an already-issued digital certificate (.EFS file) and password.

2. First Action Prediction - a new tab in Private Pair will give a prediction when a first office action will be issued. The system will even generate a letter that may be printed out.

3. Tabbed Browser- a uniform, tabbed browser interface makes it easier to navigate.

4. Supplemental Content - biosequence listings, text tables, computer program listings, etc. will also be provided.

A beta version has already been posted to the USPTO web site, and can be accessed here.

Th full presentation including audio and slides is available here (login required).

Monday, February 27, 2006

LACK OF GOOD FAITH EXPLANATION BY ITSELF NOT ENOUGH FOR INEQUITABLE CONDUCT:

(d/b/a) S&G Tool Aid Corp. v. (d/b/a) Astro Pneumatic Tool Co. (Fed. Cir. 05-1224, 1228, February 27, 2006):

S&G filed a declaratory judgment against Astro, alleging that S&G's customers did not infringe Astro's US Patent 5,259,914, and also alleged (among many other things), that the patent was unenforceable due to inequitable conduct. On summary judgment, the district court held that "there was clear and convincing evidence of materiality and intent to deceive" the the USPTO by Astro during prosecution of the application which rendered the patent unenforceable.

The court found that a competing model die grinder had been available for twenty years (the Model 220), was known to the patentee and was "material prior art" that had not been submitted to the PTO. The Model 220 allegedly contained many of the same components that were present in the ’914 patent. As a result, the court found it “clear that the Model 220 would have been material to the examiner’s analysis.” The court also noted that the Model 220 was not cumulative of other prior art before the examiner because it had elements that were not found in other prior art references. Inferring intent from the materiality of the disclosure, the court found that Astro engaged in inequitable conduct.

The Federal Circuit reversed this holding:

The issue central to the disposition of this case is whether a lack of a good faith explanation for a nondisclosure of prior art, when nondisclosure is the only evidence of intent, is sufficient to constitute clear and convincing evidence to support an inference of intent. We agree with Astro and conclude that a failure to disclose a prior art device to the PTO, where the only evidence of intent is a lack of a good faith explanation for the nondisclosure, cannot constitute clear and convincing evidence sufficient to support a determination of culpable intent.

[T]he only evidence that the district court relied upon in its determination that Astro intended to deceive the PTO was Astro’s failure to offer a good faith explanation of its nondisclosure of the Model 220. To be sure, just as a good faith explanation can be presented as evidence to refute an inference of intent, and usually is so presented, the absence of such an explanation can constitute evidence to support a finding of intent. When the absence of a good faith explanation is the only evidence of intent, however, that evidence alone does not constitute clear and convincing evidence warranting an inference of intent.

In light of all the facts and circumstances surrounding the applicant’s conduct, we conclude that Astro’s acts do not demonstrate on summary judgment that Astro had a culpable intent during prosecution. “Intent to deceive should be determined in light of the realities of patent practice, and not as a matter of strict liability whatever the nature of the action before the PTO” . . . The district court’s finding of inequitable conduct based on the nondisclosure of the Model 220 essentially amounted to a finding of strict liability for nondisclosure. Such is not the law. Even if there were evidence of gross negligence in nondisclosure, which was not found, that would not necessarily constitute inequitable conduct.

Posted by Two-Seventy-One Patent Blog at 5:01 PM 0 comments

Artigos Relacionados:

BLOGGING ON THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS: For anyone looking for an in-depth view behind the second most favorite patent litigation venue (Delaware still holds the top spot), Michael C. Smith, an litigator at the Roth Law Firm, has an excellent blog on the Eastern District of Texas. While the blog covers a myriad of topics, many of the posts focus on patent litigation before the court. It's a great site for tracking ongoing litigation without repeatedly signing into PACER to check status. What's more impressive, the blog categorizes rulings and decisions specific to each of the judges in the district, in case you need a quick snapshot of a specific judge's predilection to ruling on various pre-trial motions.

BLOGGING ON THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS: For anyone looking for an in-depth view behind the second most favorite patent litigation venue (Delaware still holds the top spot), Michael C. Smith, an litigator at the Roth Law Firm, has an excellent blog on the Eastern District of Texas. While the blog covers a myriad of topics, many of the posts focus on patent litigation before the court. It's a great site for tracking ongoing litigation without repeatedly signing into PACER to check status. What's more impressive, the blog categorizes rulings and decisions specific to each of the judges in the district, in case you need a quick snapshot of a specific judge's predilection to ruling on various pre-trial motions.

Posted by Two-Seventy-One Patent Blog at 10:23 AM 0 comments

Artigos Relacionados:

Friday, February 24, 2006

DID NTP GET "HOSED" ON THE REEXAMINATION? Yesterday, NTP released a press release, effectively saying that the USPTO took NTP's patents behind a dark alley and thrashed them with rubber hoses. Whatever you think about NTP, they may have a point. Few can deny that the reexamination proceedings, when considered in light of the pending litigation, have a certain alacrity to them on the PTO's side. While the PTO purportedly assigns special examiner teams to "high profile" reexaminations, it's rather amazing that the PTO produced concurrent 111 and 200-page decisions in one month's time from NTP filing responses to each of the Office Actions. And one can't help but wonder if the timing was somehow pre-conceived. Furthermore, regarding the '592 patent, it was unusual to see the USPTO closing prosecution, even though additional prior art was cited in the examiner's rejection.

DID NTP GET "HOSED" ON THE REEXAMINATION? Yesterday, NTP released a press release, effectively saying that the USPTO took NTP's patents behind a dark alley and thrashed them with rubber hoses. Whatever you think about NTP, they may have a point. Few can deny that the reexamination proceedings, when considered in light of the pending litigation, have a certain alacrity to them on the PTO's side. While the PTO purportedly assigns special examiner teams to "high profile" reexaminations, it's rather amazing that the PTO produced concurrent 111 and 200-page decisions in one month's time from NTP filing responses to each of the Office Actions. And one can't help but wonder if the timing was somehow pre-conceived. Furthermore, regarding the '592 patent, it was unusual to see the USPTO closing prosecution, even though additional prior art was cited in the examiner's rejection.

The perceived transgressions are numerous according to NTP, and include:

(1) The USPTO unilaterally ignored the claim construction of the Federal Circuit. This to me is a big issue. There's scant legal authority that precisely defines how court claim constructions are to be handled by the USPTO during reexamination, and what level of deference must be given. If the USPTO's position in the NTP reexam is correct (i.e. regardless of court rulings, the USPTO is free to apply a "broadest reasonable interpretation" of the claim terms), then it appears that the statutory purpose of reexaminations will eventually be frustrated. Instead of reexams being an alternative to litigation, reexams would now become a supplement to litigation for all defendants, since they all get a free and independent validity ruling on reexam. And since appellate review of PTO decisions are taken under the more deferential standard of "substantial evidence" (see Supreme Court decision In re Zurko), one can envision the possibility of the Federal Circuit being "trumped" by a PTO rejection on a claim they previously held as valid.

(2) Even though NTP prevailed through the Federal Circuit (the Supreme Court denied certiorari), the PTO refused to dismiss the pending inter-partes reexam, claiming that a "final" determination was not yet made on claim validity (see 35 U.S.C. 317(b) here). The rationale given by the PTO was somewhat strange. The denial of NTP's petition essentially stated that, while validity was not an issue in the remanded proceeding, it was "entirely possible" that new claim construction issues could arise in the district court (see 271 blog post here). This begs the question: if the USPTO is not bound to follow court rulings on claim construction, why would they care if a "possibility" existed that the court may take up a different claim interpretation on remand, even though the Federal Circuit has already ruled on the issue?

(3) The USPTO treated NTP "vastly different" for other similarly situated parties. At least one other reexamination proceeding I reviewed tends to support this contention. In reexamination proceeding 95/000093, the defendant requested reexamination after losing at the district court level. While the case was being appealed to the Federal Circuit, the patent holder moved to terminate the proceeding. While the examiner initially refused to terminate the reexamination, the examiner subsequently found that other developments and the pending action before the Federal Circuit was sufficient "good cause" that warranted suspending the reexamination in the PTO. Moreover, the decision indicated that "[a]n affirmance by the Federal Circuit will terminate these inter partes reexamination proceedings based in the estoppel provision of 35 U.S.C. 317(b)" (see "reexam Petition Decision - Granted" dated 11/17/05 here, page 6).

It appears that NTP has many valid beefs over their treatment at the USPTO. And, from an academic standpoint, it will be interesting to see how their arguments will play out at the Federal Circuit (I'm not expecting the BPAI to do anything different from the examiners). And depending on what the Federal Circuit holds, the NTP reexamination appeal could be a watershed for all future reexaminations at the USPTO.

Posted by Two-Seventy-One Patent Blog at 7:56 AM 5 comments

Artigos Relacionados:

Thursday, February 23, 2006

RIM INJUNCTION UNLIKELY? THINK AGAIN. So far, the RIM litigation has been existing in two parallel worlds between the courts and the USPTO, where "what the USPTO giveth, the courts taketh away." Yesterday's news on the USPTO issuing a final rejection on the '451 patent (which finally published late yesterday) appears to be the slow but inevitable downslide of NTP's patents.

RIM INJUNCTION UNLIKELY? THINK AGAIN. So far, the RIM litigation has been existing in two parallel worlds between the courts and the USPTO, where "what the USPTO giveth, the courts taketh away." Yesterday's news on the USPTO issuing a final rejection on the '451 patent (which finally published late yesterday) appears to be the slow but inevitable downslide of NTP's patents.

However, until the patents are revoked (i.e., NTP exhausts its appeals), the courts must treat the pending NTP patents as enforceable documents. In other words, the USPTO rejections will have little, if any, impact on the judge's decision after the parties appear in court tomorrow.

While the news from the USPTO appears good for RIM, the existing caselaw tells a different story. In last year's Federal Circuit decision in MercExchange v. EBay, the court held that district courts must grant a preliminary injunction "absent exceptional circumstances." While the case is presently before the Supreme Court, it's still good law, and you can be sure that NTP will be citing copiously from the case. The relevant portions of the ruling are reproduced below:

MercExchange challenges the district court’s refusal to enter a permanent injunction. Because the "right to exclude recognized in a patent is but the essence of the concept of property," the general rule is that a permanent injunction will issue once infringement and validity have been adjudged . . . To be sure, "courts have in rare instances exercised their discretion to deny injunctive relief in order to protect the public interest" . . . Thus, we have stated that a court may decline to enter an injunction when "a patentee’s failure to practice the patented invention frustrates an important public need for the invention," such as the need to use an invention to protect public health.

[I]n this case, the district court did not provide any persuasive reason to believe this case is sufficiently exceptional to justify the denial of a permanent injunction. In its post-trial order, the district court stated that the public interest favors denial of a permanent injunction in view of "a growing concern over the issuance of business-method patents, which forced the PTO to implement a second level review policy and cause legislation to be introduced in Congress to eliminate the presumption of validity for such patents." A general concern regarding business-method patents, however, is not the type of important public need that justifies the unusual step of denying injunctive relief.

Another reason the court gave for denying a permanent injunction was that the litigation in this case had been contentious and that if a permanent injunction were granted, the defendants would attempt to design around it . . . The court’s concern about the likelihood of continuing disputes over whether the defendants’ subsequent actions would violate MercExchange’s rights is not a sufficient basis for denying a permanent injunction. A continuing dispute of that sort is not unusual in a patent case, and even absent an injunction, such a dispute would be likely to continue in the form of successive infringement actions if the patentee believed the defendants’ conduct continued to violate its rights.

The trial court also noted that MercExchange had made public statements regarding its willingness to license its patents, and the court justified its denial of a permanent injunction based in part on those statements. The fact that MercExchange may have expressed willingness to license its patents should not, however, deprive it of the right to an injunction to which it would otherwise be entitled. Injunctions are not reserved for patentees who intend to practice their patents, as opposed to those who choose to license. The statutory right to exclude is equally available to both groups, and the right to an adequate remedy to enforce that right should be equally available to both as well. If the injunction gives the patentee additional leverage in licensing, that is a natural consequence of the right to exclude and not an inappropriate reward to a party that does not intend to compete in the marketplace with potential infringers.

Posted by Two-Seventy-One Patent Blog at 7:54 AM 1 comments

Artigos Relacionados:

Wednesday, February 22, 2006

****** NTP '451 AND '592 PATENTS INVALIDATED BY USPTO *******

According to reports, the USPTO mailed the final office action regarding NTP's US Patent 6,067,451 (see RIM report here). However, no details are provided yet on the USPTO web site (see here).

What's also interesting (but not as widely reported) is that NTP's US patent 6,317,592 is about to be nixed as well. Unlike the '451 patent, while the final rejection hasn't been posted yet on the USPTO web site, the USPTO action closing prosecution was published on February 1, and contains many of the arguments that will likely be contained in the upcoming (formal) rejection. To view the document, click here (see "Action Closing Prosecution").

The action is a whopper - over 200 pages long (although, what would you expect in a patent having 764 claims?)

The rejection hit NTP hard - new claims that NTP submitted during reexamination were rejected under 35 U.S.C. 112, first paragraph for failing to comply with the written description requirement. 5 different rejections were applied to the claims under 35 U.S.C. 102 (anticipation) and 2 different lines of 35 U.S.C. 103 (obviousness) rejections were also used.

The Patent Office stressed in the action that NTP was improperly trying to apply the claim contruction used during litigation in the USPTO proceeding. While claims during litigation are interpreted in light of the specification and prosecution history, claim interpretation in the USPTO is conducted using a "broadest reasonable interpretation."

Also, despite assertions submitted by NTP of an earlier continuation filing (US Patent 6,067,051), the USPTO maintained that the earliest filing date for the '592 patent was December 6, 1999. And despite attempts by NTP to "swear-behind" certain prior art, the Office Action concluded that defects in the declaration, along with an insufficient showing of conception, rendered the declarations ineffective to prevail.

The final patent in this mix, 5,436,960, has been rejected twice, and is expected to also get a final rejection. To view the USPTO documents on the reexamination, click here.

It doesn't get any more interesting than this - RIM and NTP are due back in court two days from now . . .

Posted by Two-Seventy-One Patent Blog at 2:36 PM 1 comments

Artigos Relacionados:

Tuesday, February 21, 2006

MERCEXCHANGE REEXAMS AND THE PENDING LAWSUIT AGAINST EBAY: The MercExchange v. EBay case, which is currently pending before the Supreme Court, is one of the most closely watched cases this year. The Supreme Court decision will answer the important question of whether or not a permanent injuction must be granted when a party is held to have infringed a U.S. patent (see amicus briefs on this subject here, courtesy of Dennis Crouch).

During litigation, MercExchange asserted three patents against EBay (US Patents 5,845,265, 6,085,176, and 6,202,051). During the district court proceeding, the '051 patent was held invalid on summary judgment for lack of written description. The '265 and '176 patents were held valid and infringed by Ebay. In the meantime, reexamination requests were launched in the USPTO on all three patents.

When the lower court's ruling was appealed to the Federal Circuit, the court reversed the ruling that the '051 patent was invalid, and remanded the case back to the district court. However, the Federal Circuit invalidated the '176 patent as being anticipated by the Keller reference, but maintained that the '265 patent was valid, and that Ebay infringed. In addition, the Federal Circuit reversed the district court's denial of MercExchange's motion for a permanent injunction with regard to the '265 patent (see Fed. Cir. ruling here). This reversal, and the rationale provided by the Federal Circuit for their ruling is the basis of the current Supreme Court case.

In the meantime, the reexaminations continue to be active in the USPTO, and may provide some interesting twists in the ongoing dispute. Each of the reexams will be summarized below.

The '051 reexam - (90/006,984): A Final Rejection was issued by the USPTO on 12/23/05, rejecting all claims. The final rejection by the examiner dismisses the arguments submitted by the patentee that the USPTO was "bound" to follow the claim construction provided by the Federal Circuit. The examiner pointed out that, while the court's claim construction may provide "guidance" for the examiner, there is no compelling caselaw that requires the examiner to follow the contruction due to the different standard of claim interpretation afforded to the USPTO ("broadest reasonable interpretation"). Surprisingly, the Office rejected the majority of claims using a 4-way obviousness combination of reference. Rejections based on written description were not present in the final office action.

The '176 reexam - (90/006,957): MercExchange filed a response to a Non-Final rejection on January 9, 2006, by substantially amending the independent claims (see "Claims" hyperlink dated 1/09/06). This could be a wild card in the EBay case. If MercExchange was given enough room to amend the claims given the prior art that was cited, it is entirely possible that they could survive reexam with new claims that could still catch EBay. It's a bit of a long shot, but anything is possible.

The '265 reexam - (90/006,956): This is a weird one. A Non-Final Action was issued back in March 24, 2005. However, there is currently no record of MercExchange haing filed a response. A 1-month extension was requested in May 2005, but the USPTO site shows no substantive submissions being made since then. Perhaps the earlier petition spat between MercExhange and Ebay caused some delay, but the reason for it taking this long is unclear. This is the "crown jewel" reexamination for EBay - should the USPTO invalidate this patent, the chances of EBay escaping infringement entirely improves exponentially.

Posted by Two-Seventy-One Patent Blog at 11:29 AM 0 comments

Artigos Relacionados:

MIXED SIGNALS FROM THE USPTO? During February's Town Hall Meeting in Chicago, the USPTO was putting forth arguments in support of the continuation restriction proposal. One of the main reasons for restricting continuations was that the purported excess of continuation applications was overwhelming patent examiners, thus slowing production.

Most practitioners rightfully questioned the extent to which continuation applications delay overall examination. The USPTO has been touting the hiring of 1,000 examiners over the coming year as evidence that the USPTO is tackling the pendency problem. Also, the encouragement of electronic filing and other initiatives are being promoted additional tools for reducing the amount of time applications wallow in the Office.

So it was somewhat surprising that, during the Town Hall Meeting, the USPTO claimed that the hiring of additional examiners would not solve production problems, and that restricting continuations was necessary as a result. In fact, the USPTO made a pretty strong point of this, as shown by one of the Power-Point slides provided at the meeting:

The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office plans to double its examiners' staff over the next five years to speed the application process, the office's director said Friday.

Jon Dudas, undersecretary of Commerce for intellectual property, says hiring 1,000 additional examiners annually over the next five years will reduce the backlog of patent applications.

Posted by Two-Seventy-One Patent Blog at 8:18 AM 2 comments

Artigos Relacionados:

Monday, February 20, 2006

RESULTS FROM THE USPTO'S OPEN SOURCE MEETING: On February 16, the USPTO conducted a public meeting with the open-source software community to discuss issues of patent quality and prior art (the meeting agenda can be viewed here). Specifically, the meeting focused on the recent effort to get the "best" prior art references to the examiner during the initial examination process to improve patent quality, and continued the discussion on issues that were raised in the December 6th meeting. Like its predecessor, the February 16th meeting was open to the public.

RESULTS FROM THE USPTO'S OPEN SOURCE MEETING: On February 16, the USPTO conducted a public meeting with the open-source software community to discuss issues of patent quality and prior art (the meeting agenda can be viewed here). Specifically, the meeting focused on the recent effort to get the "best" prior art references to the examiner during the initial examination process to improve patent quality, and continued the discussion on issues that were raised in the December 6th meeting. Like its predecessor, the February 16th meeting was open to the public.

Speakers included:

- Jack Harvey, Director of the USPTO's Technology Center 2100;

- John Doll, Director of the USPTO;

- Manny Schecter, Associate General Counsel for IBM;

- Jay Lucas, the Acting Deputy Commissioner of Patent Quality for the USPTO;

- Tariq Hafiz, Supervisory Patent Examiner for Art Unit 3623;

- Kees Cook, Senior Network Administrator for OSDL;

- Marc Erlich, Intellectual Property Counsel for Patent Portfolio Management;

- Ross Turk, Site Architect for SourceForge (who also has a blog detailing

this event);- Professor Beth Noveck of the New York Law School, the organizer of the Peer to Patent Project; and

- Rob Clark, Deputy Director of the Office of Patent Legal Administration for the USPTO.

The meeting was attended by over 200 people, and was generally well-received. Groklaw has an absolutely stunning blow-by-blow submitted by multiple attendees of the meeting, and needs to be read by anyone interested in this subject (the posts are even more amazing considering that audio recording was prohibited). Topics of discussion included the current state of third-party prior art submissions in pending applications (37 C.F.R. 1.99), as well as an examiner's perspective (Mr. Hafiz) on the examination process.

Some concerns that were discussed included:

"Prior Art Flooding" and the danger that the USPTO would quickly become

overwhelmed by submissions from the public;

"Gaming the USPTO" by bad actors using the system to intentionally obstruct otherwise valid applications; and

"Willful infringement danger," where developers would be reluctant to look at any patent data whatsoever for fear of becoming liable for willful infringement.

It is clear that the USPTO is seriously pursuing multiple fronts in an attempt to improve patent quality for software. I remain skeptical over how effective these policies will ultimately be, but it will be interesting to see the different ideas that come from the current discourse.

See complete Groklaw rundown here.

Posted by Two-Seventy-One Patent Blog at 11:36 AM 0 comments

Artigos Relacionados:

Friday, February 17, 2006

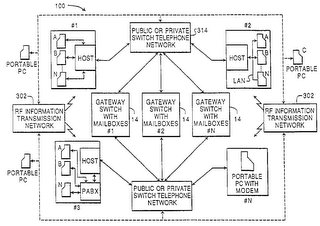

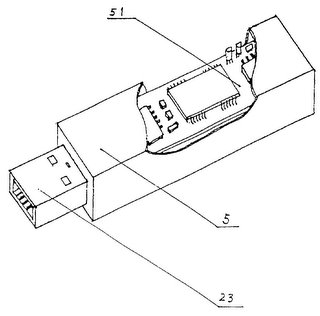

MAN BITES DOG: CHINESE COMPANY NETAC SUES U.S. COMPANY FOR INFRINGEMENT - Digital Mobile Storage Equipment manufacturer Netac Technology Co., Ltd. announced today in Beijing that the company filed a complaint in the U.S. District Court in the Eastern District of Texas on Feb. 10, 2006, alleging that U.S. company PNY infringed Netac’s U.S. patent 6, 829, 672. While Chinese companies are often accused of infringing the patents of U.S. companies, this is one of the rare cases where the roles have been reversed. And, if Netac CEO Frank Deng means what he says, this lawsuit will be the first of many that will be initiated against the multibillion dollar flash-memory market.

According to the USPTO, the '672 is one of two patents that are assigned to Netac, and there are 5 pending applications working their way through the USPTO. The '672 patent was granted in December of 2004, and claims priority to applications filed in China back in February 23, 2000 and November 14, 1999. The patent has 22 claims, with 5 being independent (see USPTO transaction history here). The claims are somewhat awkward to read, but exemplary claim 1 reads as follows:

1. An electronic flash memory external storage method, comprising the steps of:

establishing data exchange channel between a data processing system and a

portable external storage device based on USB or IEEE1394 bus upon plug said

portable external storage device into said USB or IEEE 1394 bus interface of

said data processing system;acquiring a DC power supply from said data processing system for said external storage device through said USB or IEEE1394 bus upon plug said portable external storage device into said USB or IEEE 1394 bus interface;

configuring a flash memory storage module built-in said external storage device, wherein the data storage structure of the flash memory storage module is arranged on a block basis;

directly accessing data or information in the said flash memory storage module based on USB or IEEE1394 bus standard through said established data exchange channel by implementing and processing the data access operation requests issued by users, wherein said data processing system assigning and displaying a device symbol for said external storage device and processing the operation request in magnetic disk operation format issued from users upon plug said external storage device into said USB or IEEE 1394 interface of said data processing system.

Oddly enough, Netac claims to be the first to have developed the mobile USB Flash Memory Drive, despite the fact that the USB 1.0 specification was already under development in 1997 and USB 1.1 was being distributed by 1998. Not to mention, the PC/SC Development Group was making progress in implementing USB capabilities to smart cards as early as 1996. It's no wonder that over 19 companies protested the prosecution of the patent application for having an overly-broad scope of protection

It will be interesting to see where this one is going to lead - Netac has already won infringement cases in China against Beijing Hua Qi Information Digital Technology Co., Ltd. (Product brand: Aigo) and Shenzhen Fu Guang Hui Electronics Co., Ltd. (OEM factory for Hua Qi). Additionally, Netac has pending litigation against electronic giant Sony in China, in which Netac is asking for $1.2 million in damages.

Posted by Two-Seventy-One Patent Blog at 4:21 PM 0 comments

Artigos Relacionados:

WHAT TYPE OF EXAMINER DID YOU GET? First office actions are important because they provide an initial indication of the strength of the claims in relation to the prior art, and also because the office action provides clues as to what type of prosecution experience you will likely have going forward.

While the overwhelming majority of office actions are straightforward, there are inevitably the quirky ones that leave clients and attorneys scratching their heads, wondering what exactly took place. Substantive issues aside, the type of examiner reviewing your application can often help you understand the motivations behind some of the actions. Just like litigants that size-up judges during litigation, patent practitioners should be aware of the personalities involved in the USPTO examining corps. This is especially true for foreign applicants that may view the US patent process as some weird, ritualistic exercise.

With this being Friday and all, I decided to post today on the 4 idiosyncratic examiner types that most practitioners will encounter when prosecuting applications. There are some sub-categories under each type, but the list should give you a general idea:

The "Eager Beaver" - When new examiners join the corps, they are given a trial period where they can write office actions without being on the count system. In theory, this means that they can spend as much time as they want reviewing an application and applying every section of the MPEP to the application. The Eager Beaver makes this theory reality: in cases of foreign-filed applications, office actions can be in excess of twenty pages, and are often accompanied by fastidious objections to application formalities, no matter how slight. In the overwhelming majority of cases, all of the claims will be rejected, and the Eager Beaver has no problems stringing 4-5 references together to form obviousness rejections ("when in doubt, reject using obviousness"). In essence, the examiner is being overly-cautious by making sure every perceived issue is covered in the office action. This practice usually begins to disappear after the first year of being an examiner.

Incidentally, if you want to know if you're dealing with a junior examiner, look for "the stamp." At the end of each office action, there's a signature page. If another person's name is signed alongside the examiner's signature, and has a stamp indicating "primary examiner" or "supervisory patent examiner," then you know the examiner doesn't have signatory authority (i.e., is a junior examiner).

The "Easter Egg Hunt" Examiner - After being the the examining corps for a year or so, examiners typically start to look for ways to cut corners to minimize the time they have to spend preparing office actions. After reaching a certain point however, the "minimal effort for maximum return" approach goes too far, and rejections turn into an Easter Egg hunt for the attorney trying to find the salient teaching in a broadly-cited reference. Rejections from these types of examiners will presume that applicants, being "skilled in the relevant art", will know everything that the examiner is assuming is contained in the reference, thus obviating the need to make specific references. Accordingly, the rejection will cut-and-paste the claim into the rejection and cite ridiculously broad sections of a document to support the rejection (e.g., "reference X teaches all the limitations of claim 1, as disclosed in col. 3, line 12 - col. 10, line 67; see also FIGs. 2-8"). In most cases, the rejection is simply wrong. And if that's the case, a good way to deal with this type of rejection is to set up an examiner interview, and start by requesting that he/she shows exactly where these teachings are contained in the cited passages. Chances are, the rejection will simply go away without having to formally respond on paper.

The "Francis Sawyer" - named after the character in Stripes ("the name's Francis Sawyer, but everybody calls me Psycho. Any of you guys call me Francis, and I'll kill you") this type tends to populate the more senior examiner ranks in the USPTO. After spending five or more years dealing with opportunistic attorneys, they have stopped disguising their contempt and do whatever it takes to show who's the boss during the examination process. Surly and vindictive, the Francis Sawyer will rarely pass a chance to "stick it" to an attorney, and often views the examination process as an adversarial struggle. Smart enough to be dangerous, this type will loosely follow USPTO and Federal Circuit developments and experiment his/her theories in office actions (anyone experiencing a Rule 105 "Requirements for Information" request may know what I'm talking about). Any tactics deemed successful are then disseminated to other examiners. I continue to maintain the belief that the "technical arts" test that led to the USPTO's Ex Parte Lundgren decision was started by a Francis Sawyer-type that gave this theory a run for its money.

The "Moonbeam" - saving the worst for last, this type of examiner is one that doesn't get it, and possibly never will. Deficient in technical and legal comprehension, the Moonbeam will often have you wondering what application the examiner was looking at when writing the office action. Worse yet, they have no problems dropping one line of rejections in favor of another unrelated line of rejections, regardless of their merit. In one application, I remember having eight different lines of prior art being sequentially applied to the claims during the examination process before the application was finally allowed. Only minor amendments were made to the claims after the first, and only, RCE was filed (the application was appealed once, and three separate interviews were conducted). We even tried pulling the case from the examiner, but were unsuccessful (this is a pretty difficult thing to do). It's pretty rare when you come across a Moonbeam, but when it happens, you don't soon forget it. Fortunately, these types don't last very long at the USPTO, and are pushed out pretty quickly. But in the meantime, they manage to make life a living hell for you and your client.

Posted by Two-Seventy-One Patent Blog at 11:23 AM 9 comments

Artigos Relacionados:

Thursday, February 16, 2006

IBM ANNOUNCES NEW PODCAST SERIES - "THE NEW IP MARKETPLACE": In a rather interesting move, IBM has started a podcast series that will deal with IP and patent issues. The first episode in the series discusses the characteristics of the new IP marketplace, featuring Irving Wladawsky-Berger, IBM vice president of technology strategy and innovation. You can download the podcast here.

In the maiden episode, Dr. Wladawsky-Berger explains the importance of patent quality and how the ability to share ideas stimulates innovation. He also describes the necessary characteristics of a functioning IP marketplace, including increased transparency, integrity, and mechanisms for establishing fair prices.

Dr. Wladawsky-Berger also has a rather impressive blog, where he discusses topics like IBM's collaboration with the Linux community, and provides his thoughts on improving patent quality through the OSDL project:

As its name implies, the Open Source Software as Prior Art initiative aims to make it easier to find potential "prior art" against patent applications in the millions of lines of code developed by thousands of programmers working in open source communities. OSDL will lead a team including IBM, Novell, Red Hat, SourceForge and others in developing a system that stores source code in an electronically searchable format, satisfying legal requirements to qualify as prior art. As a result, both patent examiners and the public will be able to use open source software to help ensure that patents are issued only for actual software inventions.

These initiatives bring the spirit of collaborative innovation to the really difficult challenge of improving the quality of patents. Rather than just telling the US patent office what we don't like about the current system, the public is now invited to turn its interest, even its “angst,” into a positive force, by working closely with the USPTO and patent examiners, helping them do a better job in evaluating the growing volume of applications, and helping improve the overall patent system. Patent reform is a shared, community responsibility that we should all participate in, and these new initiatives represent a major step in empowering us to do so.

While I can appreciate the blog providing "inside" information on IBM's efforts, it would actually be more interesting to hear details about the discussions that IBM had with USPTO officials. What makes them think that the Examiners will avail themselves of the search tool? Did the USPTO provide assurances regarding internal policy changes in this regard? Are they planning to tell the rest of us what is going on?

Posted by Two-Seventy-One Patent Blog at 4:05 PM 0 comments

Artigos Relacionados:

Wednesday, February 15, 2006

COURT REVERSES CLAIM CONSTRUCTION THAT PLACED "TOO MUCH EMPHASIS ON THE ORDINARY MEANING":

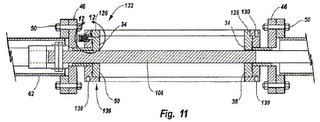

Curtiss-Wright Flow Control Corp. v. Velan, Inc. (Feb. 15, 2006: 05-1373)

Velan appealed the lower court's grant of a preliminary injunction in part over the construction of the term "adjustable" in the claimed feature reciting "an adjustable dynamic, live loaded seat coupled to said main body."

In the preliminary injunction order, the trial court concluded that the bias force on the live loaded seat could be changed in a manner that is "not limited by any time, place, manner or means of adjustment." In reaching this conclusion, the trial court relied on the ordinary meaning of "adjustable" to be "capable of making a change to something or capable of being changed." The trial court refrained from further narrowing the term, alleging that claim differentiation prohibited the court from doing so, and also alleged that further limitations would impermissibly narrow the claim to the structure of the preferred embodiment.

The Federal Circuit, while commending the lower court's restraint, disagreed. After applying a Phillips analysis to the claims in light of the specification, the Federal Circuit concluded that the disclosure defined the term "adjustable" to mean that the dynamic, live loaded seat can be adjusted while the de-heading system is in use.

Furthermore, the Federal Circuit reasoned that the district court’s construction of "adjustable" rendered that limitation nearly meaningless:

This court finds it difficult, if not impossible, to imagine any mechanical device that is not "adjustable," under the ordinary meaning of that term adopted by the district court. Almost any mechanical device undergoes change (for instance, when dismantled to replace worn parts) when no consideration is given to the "time, place, manner, or means of adjustment."

Thus, while the district court may have been correct that a device encompassed by claim 14 of the ’714 patent need not have an adjustment mechanism, it went too far in completely eliminating any constraints on the "adjustable" limitation. Moreover, the district court’s construction actually creates a redundancy: if "adjustable" means adjustable at any time and in any way, it is hard to imagine any meaning for the term because without limitations on time or manner of adjustment, all structures are "adjustable."

Regarding the issue of claim differentiation between independent claims, the Federal Circuit provided that two considerations generally govern this claim construction tool when applied to two independent claims:

(1) claim differentiation takes on relevance in the context of a claim

construction that would render additional, or different, language in another

independent claim superfluous; and(2) claim differentiation "can not broaden claims beyond their correct scope.

Finding that both of these considerations weighed against the district court's construction, the preliminary injunction was vacated and the case was remanded.

Posted by Two-Seventy-One Patent Blog at 4:04 PM 0 comments

Artigos Relacionados:

EFF ATTACKS CLEAR CHANNEL'S '729 PATENT: Yesterday, the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) announced they have filed a reexamination request on US Patent 6,614,729, titled "System and method of creating digital recordings of live performances." The patent is assigned to Instant Live LLC, which is part of Clear Channel Communications.

In the past few years, fans leaving some concerts have discovered that instead of getting a poster or T-shirt, promoters are offering a live recording of the show they just attended as a souvenir. This practice has blossomed into a lucrative business, and like everything else in commercial music, Clear Channel has now positioned itself as a gateway for the entire industry.

Accordingly, the EFF has designated the patent as one of the "10 Most Wanted" on their Patent Busting Project (never mind the fact the Clear Channel has single-handedly transformed the entire radio industry into a vapid, homogeneous musical wasteland - there, I said it).

The '729 patent has only 5 claims. Claim 1 recites the following:

1. An event recording system, comprising:

(i) an event-capture module to capture an event signal and transform it into a primary event file that is accessible as it is being formed;

(ii) an editing module communicatively connected to the event capture module, wherein the editing module accesses and parses the primary event file into one or more digital track files that can be recorded onto a recording media; and

(iii) a media recording module communicatively linked to the editing module for receiving the one or more digital track files, the media recording module having a plurality of media recorders for simultaneously recording the one or more digital track files onto a plurality of recording media.

The prior art found by the EFF deals with a company called Telex, and their EDAT digital mastering hardware/software toolkit, which EFF claims discloses the feaures of claim 1, and predates the filing of the patent application by more than 1 year. The EFF is working in conjunction with Theodore C. McCullough of the Lemaire Patent Law Firm and with students at the Glushko-Samuelson Intellectual Property Clinic at American University's Washington College of Law, in the effort to revoke the patent based on this and other evidence.

A copy of EFF's reexamination request may be downloaded or viewed here.

The prosecution history of the '729 patent can be downloaded or viewed here.

As a side note, it appears that the EFF overlooked US Patent 6,917,566, which is a continuation of the '729 patent, and has somewhat similar claims. Also, Instant Live also filed another continuation (11/119,182) back in April of 2005, which also has a similar claim scope (known in patent parlance as "milking it"). Interestingly, the '566 patent has one reference to the Telex system, although the citation merely cites the company's general web page. Even if the EFF knocks out the '729 patent, the industry will continue to be vulnerable to Clear Channel's '566 patent and possibly the '182 application that is pending in the USPTO.

Posted by Two-Seventy-One Patent Blog at 8:33 AM 0 comments

Artigos Relacionados:

Tuesday, February 14, 2006

JAPANESE CHIPMAKERS TURN TO . . . . TROLLING? For years, larger Japanese companies have been some of the most prolific filers of patents throughout the world, particularly in the U.S. While they continue to amass patents on key technologies, Japanese companies have traditionally eschewed "U.S.-style" litigation, in favor of traditional negotiation an licensing.

It appears that is starting to change, at least in the short-term.

As competition in the memory-chip sector heats up, Japanese companies are increasingly turning to litigation to protect their hard-won patents. In light of Korea's speedy ascent in the technology and IP sectors, Japanese chipmakers have ramped-up the number of patent infringement cases in an attempt to beat back the competition and to squeeze more value from technologies that took years and billions of yen to develop.

In the world of DRAM chips, Japanese chip manufacturers dominated this industry in the 1990s, but nearly all of them - with the exception of Elpida Memory Inc. - have since exited the business (Elpida being a joint venture between NEC and Hitachi). Today, South Korea's Samsung Electronics and Hynix are now the world's two largest makers of DRAM chips, while Elpida ranks fifth behind U.S.-based Micron Technology Inc. and Germany's Infineon Technologies AG. In the hot-selling NAND flash memory business, Samsung ranks No. 1 and Toshiba No. 2, but the Japanese company's lead over third-ranked Hynix is narrowing.

Recently, Japan's Toshiba Corp. filed a lawsuit in October with the U.S. International Trade Commission against South Korea's Hynix Semiconductor Inc. alleging that the South Korean chip maker infringed on its flash memory patents.

Also, Matsushita Electric Co. filed suit against South Korea's Samsung Electronics Co., alleging patent infringement related to DRAM, chip technology. The lawsuit was filed - where else - in the Eastern District of Texas, Marshall Division.

The interesting rub is that Matsushita stopped making DRAM chips in 1998. Matsushita has not provided further comment since filing the lawsuit in late January.

Posted by Two-Seventy-One Patent Blog at 8:29 AM 0 comments

Artigos Relacionados:

Monday, February 13, 2006

ABOUT THAT BLACKBERRY WORKAROUND . . . Towards the end of last week, RIM announced their "workaround" to get past NTP's patents, just in case the district court decides to grant an injunction against the wireless e-mail giant.

The software fix is called the "BlackBerry Multi-Mode Edition" and works by changing the part of the network where e-mails are stored. Under the fix, the software is capable of operating in different modes that can be remotely activated by RIM through its Network Operations Center (NOC). If the injunction is ordered, RIM will activate a "U.S. mode" remotely via the NOC. The workaround designs would then automatically be applied for each handset and corporate e-mail server containing the Multi-Mode Edition software update. If the injunction falls through, the software will operate in "standard mode," which is identical to how the current BlackBerry software works today.

Currently, when a device is out of wireless coverage range and can't immediately get e-mail access, RIM's service stores incoming messages on computers at one of its two NOCs. When the device comes back into coverage range, the e-mails are then forwarded automatically. Under the workaround, these waiting e-mails would be stored somewhere else, such as a firewall server of a company or carrier network (see more here and here).

Further details of the workaround are sketchy, and most techies can only speculate as to how the message routing really works. A large part of the infringement of the NTP patents is based on the e-mails being stored at the NOC, and there seems to be a consensus agreeing that the workaround will overcome NTP's patents in principle.

However, it is nevertheless a close call, and it is evident that the workaround was instituted from a position of weakness from RIM's side (even though RIM has claimed to have filed a patent on this technology). From what is currently known about the fix, when the patch is installed, the header and message aren't pushed to the device, but a notification message is sent that looks like the header of the email. The message doesn't get pulled to the device until the notification message is activated by the user to read the email message, which can create a 1-2 second delay.

RIM's move seems to be geared more towards buying time, hoping that the USPTO's reexamination (and the inevitable appeals) will result in a bunch of invalid patents, while the software fix runs its course. Even with the workaround, there is nothing that would stop NTP from filing new lawsuits against RIM regarding the workaround. But to do this, NTP would have to spend additional time pursuing this litigation. There's also the question whether this fix may violate third-part patents (e.g., Visto).

More importantly, this fix would appear to put RIM in a precarious position when arguing against the potential injunction. Since RIM is touting this fix as "transparent" to the users, it seems like a difficult task to argue that an injunction would be catastrophic for RIM users while at the same time promoting a workaround that is claimed to work as well as the infringing process . . .

Posted by Two-Seventy-One Patent Blog at 8:08 AM 0 comments

Artigos Relacionados:

Thursday, February 09, 2006

UK PATENT OFFICE PUBLISHES RESULTS OF "EXPERT OPINIONS" ON PATENTS: Last autumn, the UK Patent Office initiated a new opinions service which allows anyone to ask the Patent Office for an "expert opinion" on an issue of patent infringement or validity.

UK PATENT OFFICE PUBLISHES RESULTS OF "EXPERT OPINIONS" ON PATENTS: Last autumn, the UK Patent Office initiated a new opinions service which allows anyone to ask the Patent Office for an "expert opinion" on an issue of patent infringement or validity.

The service is intended to help parties test the strength of their arguments at the Patent Office before, or instead of, resorting to litigation. Both sides of a dispute are allowed to submit arguments to a senior examiner before the opinion is finally issued. Anyone may request an opinion on any UK patent, or European patent which designates the UK. The cost for the service is £200 and after the request is filed, there is a short period for the public to make further observations on the request, and for the requester and patentee to make arguments in reply. Currently, the time period for an opinon to issue is 12 weeks.

So far, a total of six opinions have been requested since the service was launched, and requests have been made by both patent holders and third parties. This program has generated a great deal of interest from other UK patent holders and intellectual property professionals, and it is anticipated that the requests will increase as more information about the program becomes available.

The UK Patent Office has made the opinions publicly available on their web site, and include both infringement and invalidity opinions. To view the opinions, click here.

Posted by Two-Seventy-One Patent Blog at 9:30 AM 0 comments

Artigos Relacionados:

NEW SWEDISH POLITICAL PARTY FORMED ON ANTI-IP PLATFORM: In preparation for September's general election, 34-year old IT engineer Richard Falkvinge decided to start a political party on New Year's Day. After setting up an online support site, his initial goal was to muster 2,000 online suporters by February. In 36 hours he had 4,700, and had to temporarily shut the site.

NEW SWEDISH POLITICAL PARTY FORMED ON ANTI-IP PLATFORM: In preparation for September's general election, 34-year old IT engineer Richard Falkvinge decided to start a political party on New Year's Day. After setting up an online support site, his initial goal was to muster 2,000 online suporters by February. In 36 hours he had 4,700, and had to temporarily shut the site.

Thus was born the Pirate party, Sweden's newest political organization. The move came just seven months after Sweden passed a law banning the sharing of copyrighted material on the Internet without payment of royalties, in a bid to crack down on free downloading of music, films and computer games. On the party web site, it states that its sole campaign issue will be "abolishing intellectual property" and decriminalizing Internet file-sharing.

According to Falkvinge, "[t]hirty years ago, the cost of production of music was astronomical. Now anyone can do it in their basements. The multinationals are no longer needed and are fighting back. Citizens are being criminalized." As for patents, "companies innovate because of the market and because they have to . . . by abolishing patents, we will free Swedish firms to innovate."

Posted by Two-Seventy-One Patent Blog at 8:01 AM 0 comments

Artigos Relacionados:

Wednesday, February 08, 2006

FEDERAL CIRCUIT CLARIFIES WHEN A MISSTATEMENT OR OMISSION IS "MATERIAL":

Digital Control Inc. v. The Charles Machine Works - Feb 8, 2006 (05-1128)

Digital Control, Inc. appealed the decision of the district court for the Western District of Washington finding that 3 of the patents in suit were unenforceable for inequitable conduct. The district court's determination of inequitable conduct was premised on the materiality of both misstatements made in a Rule 131 declaration previously filed by the patentee and the failure to disclose prior art.

During prosecution of the patents, prior art was cited, and the patentee (Digital Control) overcame the rejection by filing a Rule 131 declaration, claiming that the inventor conceived and diligently reduced to practice the subject matter of the invention prior to the effective filing date of the prior art. The problem was that the inventor never actually made the prototypes he claimed to have had in his declaration.

Also, the inventor had in his possession prior art that was cited in a pending continuation application, but was not disclosed to the USPTO during the prosecution of the asserted patents (all 3 patents had the same disclosure). This art was subsequently used by the Examiner to reject the continuation application.

Finding that the combination of events rose to the level of inequitable conduct, the district court granted summary judgment against Digital Control, and ruled the patents unenforceble.

Regarding the misstatements in the Rule 131 declaration, the court repeated that "affirmative misrepresentations . . . in contrast to misleading omissions, are more likely to be regarded as material." As such, the granting of summary jusgment was proper in light of the lower court's record.

However, regarding the issue of whether the omission of prior art was "material," the court reversed the granting of summary judgment because (1) the scope and content of prior art and what the prior teaches are questions of fact, and (2) the lower court did not provide a clear record of which facts were determinative of the finding of inequitable conduct.

Also, the court noted that Rule 56 issues of candor and good faith were changed back in 1992, when the PTO created an arguably narrower standard of materiality. Under the old rule, the courts have held "that materiality for purposes of an inequitable conduct determination require[s] a showing that 'a reasonable examiner would have considered such prior art important in deciding whether to allow the parent application.'"

Under the new (post-1992) rule, the test for materiality was changed where

[I]nformation is material to patentability when it is not cumulative to information already of record or being made of record in the application, and

(1) It establishes, by itself or in combination with other information, a prima facie case of unpatentability of a claim; or

(2) It refutes, or is inconsistent with, a position the applicant takes in:

(i) Opposing an argument of unpatentability relied on by the Office, or

(ii) Asserting an argument of patentability.

The question was raised whether the "new" rule supplanted the old "reasonable examiner" rule. After providing a detailed analysis, the court concluded that it did not:

That the new Rule 56 was not intended to replace or supplant the "reasonable examiner" standard is supported by the PTO's comments during the passage of the new rule. The PTO noted that the rule "has been amended to present a clearer and more objective definition of what information the Office considers material to patentability" and further that "[t]he rules do not define fraud or inequitable conduct which have elements both of materiality and of intent."

In this case, the district court, faced with the two versions of Rule 56, determined that the new Rule 56 standard was essentially the same as the "reasonable examiner" standard, and thus applied the "reasonable examiner" standard and our case law interpreting that standard. Summary Judgment, slip op. at 9-19. Because the "reasonable examiner" standard and our case law interpreting that standard were not supplanted by the PTO's adoption of a new Rule 56, when reviewing the district court's decision, we will do the same.

Posted by Two-Seventy-One Patent Blog at 12:35 PM 0 comments

Artigos Relacionados:

Tuesday, February 07, 2006

FY'07 BUDGET ALLOWS USPTO TO KEEP MORE MONEY: One of the biggest misconceptions about the USPTO is that it is taxpayer funded. It's not. Instead, funding for the USPTO is provided by fees charged to applicants and other persons taking advantage of services the USPTO provides (i.e., reexamination requests, protests, etc.). During the patent application process, applicants are required to pay various fees for filing applications, examiner searches, extensions of time, filing RCE's/continuations, issue fees and even have to pay "maintenance fees" 3.5, 7.5 and 11.5 years after a patent has issued to keep it in force. All this money is then (presumably) sunk back into USPTO operations to upgrade and improve operations.

Since the USPTO became fee-funded (back in the early 1980's), the U.S. Congress has made a habit of diverting these funds to general government operations, without any recompense to the USPTO. In theory, the fee-funded system provided the USPTO with enough flexibility to accommodate increases in patent filings by hiring more personnel and expanding operations - as more applications get filed, the USPTO coffers fill up with additional fees.

Unfortunately, when the Federal Government pinches these funds from the USPTO, the Office is left without the means to properly examine waves of patent applications being filed during a particular period of time.

Accordingly, a recent budget proposal submitted by the Bush Administration provides that the USPTO would receive $1.8 billion under the fiscal 2007 budget, which is an increase over the $1.7 billion that the administration requested and lawmakers approved in fiscal 2006.

Also, the administration proposed that PTO be able to keep the fees it collects from patent and trademark applications. Congress approved a two-year increase and retention of PTO fees in fiscal 2004 . In the 2007 budget proposal, this increase was extended another year, and plans are underway to introduce legislation that would make the change permanent (H.R. 2791, S.1020).

Another interesting aspect of this legislation is that electronic filing will be "encouraged" for all applicants by reducing fees on documents that are filed electronically with the USPTO.

Projections have also been made where it is anticipated that the USPTO will receive 444,014 patent applications in fiscal 2007, an increase from the 414,966 applications expected in fiscal 2006. The fiscal 2007 budget also projects that the office will spend $4,196 to approve each application. That number would be slightly less than the $4,279 in fiscal 2006, due to the presumed increase in electronic filing.

See summary here.

Posted by Two-Seventy-One Patent Blog at 12:27 PM 1 comments

Artigos Relacionados:

Monday, February 06, 2006

WIPO ISSUES REPORT ON PCT FILINGS: With all the focus lately on US patent filings, WIPO issued a report today on the number of international patent filings being made by individual countries and corporations. Specifically, the study found that east-Asian countries, such as Japan, Korea and China accounted for the largest jump in Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) filings anywhere in the world:

“The rate of growth from Japan, Republic of Korea and China continues to be exceptional, reflecting the rapidly expanding technological strength of those countries. Since 2000, the number of applications from Japan, Republic of Korea, and China, has risen by 162%, 200% and 212%, respectively,” said Mr. Francis Gurry, WIPO Deputy Director General who oversees the work of the PCT.More notably, the Republic of Korea overtook the Netherlands as the 6th biggest user of PCT applications and China dislodged Canada, Italy and Australia to take the position of 10th largest PCT user. In 2005, over 134,000 PCT applications were filed, representing a 9.4% increase over the previous year.

Furthermore, WIPO issued a list of companies recognized as "top PCT filiers." The top ten include:

1 (NL) KONINKLIJKE PHILIPS ELECTRONICS N.V. - 2492

2 (JP) MATSUSHITA ELECTRIC INDUSTRIAL CO., LTD. - 2021

3 (DE) SIEMENS AKTIENGESELLSCHAFT - 1402

4 (FI) NOKIA CORPORATION - 898

5 (DE) ROBERT BOSCH GMBH - 843

6 (US) INTEL CORPORATION - 691

7 (DE) BASF AKTIENGESELLSCHAFT - 656

8 (US) 3M INNOVATIVE PROPERTIES COMPANY - 603

9 (US) MOTOROLA, INC. - 580

10 (DE) DAIMLERCHRYSLER AG - 567

Interestingly, only 10 U.S. companies appear in the top-25, and IBM, who has consistently maintained the no. 1 U.S. patent filer position in the U.S. for the last 13 years, ranks 22nd in PCT filings.

See report here.

Posted by Two-Seventy-One Patent Blog at 3:37 PM 0 comments

Artigos Relacionados:

Friday, February 03, 2006

A MODEST PROPOSAL FOR PATENT REFORM: EXPAND DUTY OF CANDOR TO POST-GRANT ACTIVITY: With all the concerns over "bad" patents and serial patent litigation, there have been many proposals put forth to overhaul the US patent system. One of the biggest problems in the current reform movement is that it is very difficult to provide a clear statutory definition on who is trying to abuse the patent system (i.e., Lemelson) versus someone who is legitimately enforcing a constitutional right (i.e., the "power to exclude").

Currently, the USPTO imposes a duty of candor and good faith under 37 C.F.R. 1.56, where, if any information that is material to patentability is known by the applicant during examination, the applicant must disclose this information to the USPTO or subsequently risk a charge of inequitable conduct. If this happens, the patent is rendered unenforceable.

It's a good rule, which generally keeps applicants honest during the examination of their patent applications (oddly enough, the EU doesn't have such a requirement). However, once the patent issues, the duty is discharged, and no further submissions are required. For example, if your patent issues, and a week later you, or someone else, discovers prior art that kills your application, there is no requirement that forces a person to disclose the prior art to the USPTO. As such, the public only has a limited snapshot of the state of the art as it pertains to the issued patent.

Since the USPTO has limited time and resources to search for prior art, it is automatically assumed that the art cited during prosecution is not necessarily the "best" prior art out there.

The software industry is working on ways to make more prior art documents available in specific technological fields (see USPTO-open source collaboration here). But this is an inefficient process. Just because you pump out lots of documents doesn't mean that people reading those documents will interpret them correctly and/or know how to apply those documents towards a specific patent.

What is needed is a system where the state of the art can be determined, not just for a specific technological field in which a patent issued, but to the patent itself.

Which brings me to my proposal:

Proposed rule for "Duty to Disclose Post-Issue Information":

A patentee has the duty to disclose all litigation activity involving the issued patent, and further disclose all submitted arguments directed towards claim scope, as well as any patents or publications asserted as invalidating prior art during litigation.Under this proposal, the USPTO would modify its on-line web site (as well as PAIR) to have a link to "Post-Issue Information." Once it is clicked, the information discussed below would be displayed.

How the duty works:

(1) If a patent is asserted in district court, the patentee is under the obligation to notify the USPTO of the case name, court, and docket number, along with a copy of the complaint. That's it. A small filing fee would be charged for the filing (of course), and the notification of litigation activity would be marked for the patent. This one is easy, since courts already give notice to the USPTO Commissioner of pending litigation, and all the PTO would have to do is incorporate this directly to their web site.

(2) If patents or publications are alleged to be invalidating prior art, all of those documents must be submitted to the USPTO within a set period of time (say, 1 month, with extensions), along with a copy of the court document identifying the prior art. It does not matter if a judge or jury has not considered or ruled on the prior art - the patentee must submit the documents. Again, the patentee would be given a set period of time (1 month, with extensions) to make the submission.

(3) All final copies of Markman briefs submitted to the court, as well as any Markman ruling, must be filed with the USPTO within 2 months (with extensions). "Final" version means either (a) the latest copy, if the case was subsequently settled, or (b) the version containing the last-entered amendments prior to the Markman hearing.

How the disclosures would be used by the USPTO:

As mentioned earlier, when you pull up a specific patent on the USPTO web site, a tab would be provided for "post-issue activity." Once it is clicked, you would be provided with two options: (1) litigation activity, and (2) post-issue prior art. Clicking the first option would provide a list of all the litigation that has been filed on the patent, along with a link to any/all of the Markman documents. Clicking the second option would provide a hyperlinked list of all the prior art, similar to the current listing the USPTO provides on the website.

The USPTO would only be charged with processing and maintaining these documents, and making sure they correctly display the information on the USPTO website. No examiners would be involved in reviewing the prior art documents.

How the proposal will be enforced:

While I haven't slogged through the finer details of this part yet, the only way for this proposal to work would be to attach some form of inequitable conduct or even a patent misuse ramification for failing to comply. By not providing the required "notice to the public" regarding your post-issue activities, you either (1) lose the right to collect damages while the defect is present, or (2) lose the right to sue a named defendant altogether, if proper prior notice wasn't given to the USPTO. Since these areas are not really codified in the U.S.C. (i.e., this is mostly court-made law), there would have to be some additional laws drafted to cover this aspect.

With regard to the filings in the USPTO, this could be handled through the USPTO fee schedule. Thus, if a patentee intends to hold back information to try and prejudice potential defendants (by filing the documents in the last minute, and then suing), the USPTO can set up an arrangement where, for example, the patentee would be charged $500 a month after the filing due date up to three months, $1,000 a month from 3-6 months, and $5,000 a month thereafter. By matching the court document with the filing date, the USPTO could easily determine the time lag between the date of disclosure and the submission date to the USPTO.

What are the benefits?

The primary benefit of this is information consolidation. All of the aforementioned information is already available for anyone that wants to go dig for it. However, collecting and processing the information can be time consuming and can get really expensive, depending on how actively a patent is being litigated. By making this information centrally available through a web portal, just about anyone having some knowledge of patents can quickly assess (1) how aggressive the patentee is, (2) the types of companies that are being targeted, (3) whether the lawsuits are settled quickly, (4) How the claim language is being interpreted, and (5) the quantity and quality of prior art that was found after the patent issued.

Furthermore, the burden and cost of implementing this proposal falls mostly on the litigant, but is relatively painless to comply with. As a practical matter, all the patentee has to do is make a copy of the relevant documents, provide a "post-issue IDS" if necessary, and mail it off to the USPTO. While I doubt the collected USPTO fees will be sufficient to cover the cost of reorganizing the USPTO servers and databases, I think the cost-to-benefit analysis still comes out strongly in favor of the proposal.

Another benefit is that this proposal incorporates all the "floating" prior art that results when cases are settled during litigation (which is the overwhelming majority of patent cases). By forcing these documents into the USPTO, the public gets a collective state-of-the-art snapshot that "runs with the patent" so to speak. And the more you litigate, the greater the likelihood will be that potentially damaging prior art will surface. If your patent is as strong as yout think it is, you won't have problems. But if you try to repeatedly enforce a dodgy patent, it is likely that the prior art will eventually (and quickly) catch up with you.

Reexamination practice could be energized by this as well. Since the current and "best" prior art is associated with, and displayed alongside the patent, you could determine whether a particular patent is ripe for reexamination. Since the post-issue prior art was presumably reviewed by one or more patent attorneys prior to being submitted in court, there is at least some assurance that the quality of the prior art is relatively high. This could also provide incentive for the USPTO Director to unilaterally issue reexams without unduly taxing examiner resources.

Furthermore, by allowing people to build off of previous defendants prior-art searching and work product, this could provide significant savings to smaller companies, who won't necessarily have to rebuild the wheel when facing potential litigation. This could also reduce the time for researching patents for opinion work as well. Finding invalidating art is one of the most important and difficult aspects of patent litigation - by streamlining this process to the USPTO, companies could have an important tool to quickly assess the post-issue activities of a patent without dispatching armies of lawyers every time they get a demand letter.

Again, this post identifies a concept that is obviously a work in progress. I'm sure there are aspects of this that I haven't considered completely yet. However, many of the people I've bounced this idea off of have been very receptive. If you have any thoughts on this topic (good or bad), I'd like to hear from you. Feel free to e-mail me: pzura@bellboyd.com

P.S. I have no intention of filing a patent application on this . . .

Posted by Two-Seventy-One Patent Blog at 8:03 AM 1 comments

Artigos Relacionados:

Thursday, February 02, 2006

USPTO GRANTS REEXAM ON FORGENT'S JPEG PATENT AT THE BEHEST OF PUBPAT: Last November, the Public Patent Foundation ("PUBPAT") filed a reexamination request with the USPTO, asking it to invalidate Forgent's "JPEG" patent (US 4,698,672).

PUBPAT is a not-for-profit legal services organization that "represents the public's interests against the harms caused by the patent system, particularly the harms caused by wrongly issued patents and unsound patent policy." According to the organization, PUBPAT provides the general public and specific persons or entities otherwise deprived of access to the system governing patents with representation, advocacy and education.

Lately, PUBPAT has been making headlines acting as the agent provocateur of the anti-software movement.

As this blog previously predicted, the USPTO granted the reexam request. According to the USPTO website, this reexam is the first one ever requested on the '672 patent despite a literal tidal wave of litigation (see reexam documents here). The reexamination request cites another Forgent patent (i.e., Compression Labs), US Patent 4,541,012, as invalidating art under 102(b).

According to the Reexam order, the examiner found that there was sufficient evidence to show a substantial new question of patentability, and that the reexam would be placed under "special dispatch" (think "rocket-docket"). In the next 2-3 months, the Examiner should be issuing a Non-Final rejection.

Posted by Two-Seventy-One Patent Blog at 4:57 PM 0 comments

Artigos Relacionados:

Wednesday, February 01, 2006

LEGISLATION PROPOSES MANDATORY SANCTIONS FOR "FRIVOLOUS" LAWSUITS: The U.S. Senate is currently reconsidering legislation (H.R. 420) to amend Rule 11 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure to make sanctions mandatory against parties and attorneys who file frivolous lawsuits.

LEGISLATION PROPOSES MANDATORY SANCTIONS FOR "FRIVOLOUS" LAWSUITS: The U.S. Senate is currently reconsidering legislation (H.R. 420) to amend Rule 11 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure to make sanctions mandatory against parties and attorneys who file frivolous lawsuits.

In January, U.S. Rep. Lamar Smith reintroduced the "Lawsuit Abuse Reduction Act" after the House passed the measure in October 2005 by a 228-184 vote. Prior to that, the House passed a similar measure that was ultimately stalled without resolution. The proposed law is the latest effort in the tort reform movement to protect businesses against frivolous lawsuits, and, in case you weren't aware, patent infringement is a tort.

While the law isn't specifically directed towards patent litigation, there are portions of this bill that may have an impact.

For one, the bill would reinstate the imposition of mandatory sanctions for parties and attorneys who file frivolous lawsuits. Prior to 1993, the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure provided mandatory sanctions ("Rule 11 sanctions") on attorneys who filed abusive or harassing litigation. Subsequently, the rules were changed to provide sanctions only on a discretionary basis by the presiding judge. Also, a 21-day "safe harbor" provision was added to allow an attorney 21 days to withdraw a lawsuit alleged to be frivolous, without any repercussions. The proposed law would do away with these amendments.

The law also provides a "three strikes" provision, where, if a federal district judge determines an attorney has violated Rule 11 three or more times, the judge "shall suspend that attorney from the practice of law in that federal district court for one year."

Furthermore, an anti-forum-shopping provision was inserted to prevent plaintiff's attorneys from "gaming" the system to file cases in courts where sympathetic judges preside (defendants affectionately refer to these courts as "judicial hellholes"). However, after looking at the current version of the bill, it appears this provision won't apply to patent cases.

The relevant portion of the proposed law states that a personal injury claim filed in State or Federal court may be filed only in the State and, within that State, in the county or Federal district in which:

(1) the person bringing the claim resides at the time of filing or resided at the time of the alleged injury;

(2) the alleged injury or circumstances giving rise to the personal injury claim allegedly occurred;

(3) the defendant's principal place of business is located, if the defendant is a

corporation; or(4) the defendant resides, if the defendant is an individual.

However, the proposed law defines the term "personal injury claim" to mean a civil action brought under State law by any person to recover for a person's personal injury. Since patent law is governed by federal law, it appears that patent infringement lawsuits will be exempted (you can breathe easier now, E.D. Texas).

To get more details on the proposed law, click here.